|

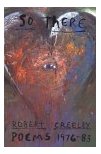

Contents » Cover |

||

|

Reviews

Robert Creeley's So There collects three earlier books: Hello, Later, and Mirrors. Although these poems have appeared in print before So There is a new book. Bound together these poems engage a counterpoint whose intricacies, harmonies, and dissonances entail important qualities of Creeley's later poetics. Reviewing Pieces in 1970, Denise Levertov noted a relaxation in Creeley's conception of lyric closure: Its very sprawl and openness, its notebook quality, its absence of perfectionism, Creeley letting his hair down, is in fact a movement of energy in his work, to my ear: not a breaking down but a breaking open. In So There this breaking open grows in scope, gaining force by echo and disjunction not only across poems, but across books. Hello records Creeley's wanderings through Asia. For Creeley, geographic wandering and a wandering mind are of a piece (from "Hamilton Hotel"):

Magnolia tree out window Memory itself is the topic of this poem. The poem treats the gap between here and there, now and then: "here in Hamilton— / years and years ago / the house, in France . . ." Lineation and punctuation reinforce the disjunction of present and past. The fact of memory, in other words, bespeaks a distance from Creeley's younger self, a travelling away from previous lives. In Mirrors Creeley resumes this motif, in the poem "Oh Max," asking: "What's Memory's / agency—why so much / matter." Memory's agency appears in these poems not as a function of intention, but of accident. To wander and to wonder, these become a single action. In "Later 10" we read:

. . . But now— Loading our ear with assonance and lexical repetition these lines blur their principal verbs. Both technically and thematically, then, Creeley elides the forms that serve to distinguish wondering from wandering. The slippage between wandering and wondering, Creeley's engagement with accident and memory, achieves its most compelling articulation in the echoes that span So There. The problem of recollection is enacted in the very fact of the book as a collection. Repetition (and its frustration) allows words and themes to act in concert, without sacrificing their singularity. The work of echo is nothing new to Creeley's poetics. But what is new is the relaxation, the expansion that enables these echoes. In "Was that a Real Poem?" Creeley describes his development as a poet: "The intensive, singularly made poems of my youth faded as, hopefully, the anguish that was used in the writing of so many of them also did."* So There bespeaks Creeley's current distance from his youthful poetics not only by recording memories, but by giving those memories room to wander.

|

|||||